Mitigating gender bias in machine translation: adapt, then correct

Machine translation struggles to translate people’s gender. Instead, it reflects gender bias from huge numbers of training sentences. But retraining computation-hungry machine translation from scratch is inefficient, and removing subtle imbalances from huge datasets may be impossible.

We decided instead to try mitigating biased behavior by adapting existing models to new data, sidestepping both problems. Read on for a summary of how we did this and what we found, or see our ACL 2020 paper, Reducing gender bias in neural machine translation as a domain adaptation problem, for all the details.

Translating (human) gender

German, Spanish, Hebrew, Arabic and Russian are just a handful of the many languages which have rich grammatical gender. For these languages a sentence can only be correct if its words have consistent grammatical gender.

For some words, like “table”, gender is fixed. For words referring to a person, though, grammatical gender can depend on the person’s gender. Human-referent words like this exist in English, often as occupations — for example, “actress” as the feminine form of “actor”.

In languages with richer grammatical gender than English, far more human-referent words are gendered. For these languages, machine translation needs to translate human gender correctly and consistently. And as identified in recent years, notably by Stanovsky et al, machine translation fails at this.

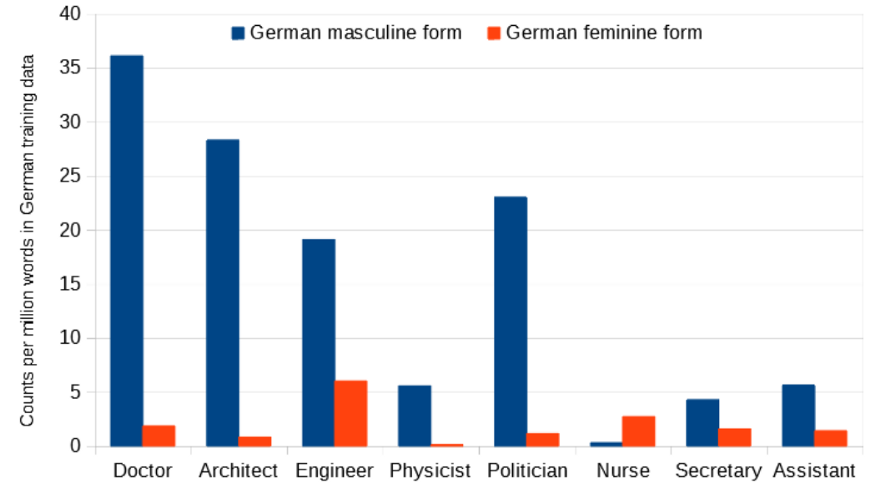

Instead, machine translation works in a way that looks a lot like gender stereotyping. Doctors and engineers tend to be translated into the masculine form by default, while nurses and secretaries tend to be translated to the feminine form.

Why does machine translation stereotype gender?

Machine translation systems are trained to translate from one language to another by being “shown” pairs of sentences and their translations. Millions of examples might be required for good performance.

When we look at words that are gendered in the target language, like “doctor”, we find that they are often skewed towards examples with either a masculine or feminine gendered form.

For example, there are far more examples of masculine doctors in the German training examples. This may be that there are more male doctors in the dataset, or it may be due to a convention of using the masculine as the default if there’s no other context, as in the sentence “Doctors agree on this.”

So when translating new sentences, a “best guess” can end up defaulting to that stereotype.

When does stereotypical translation happen?

Interestingly, this type of gender stereotyping through translation does not only happen for ambiguous sentences where there’s no way of telling gender.

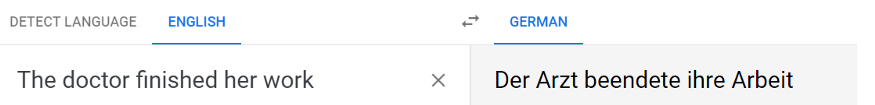

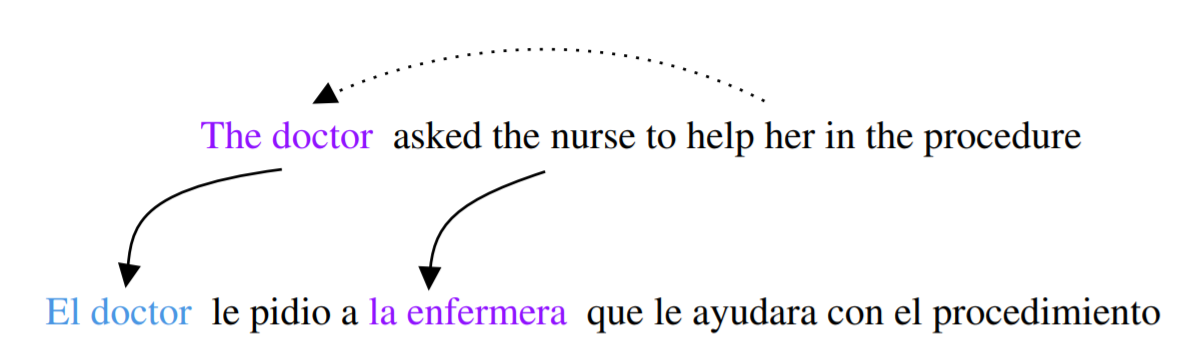

It also happens when there’s a pronoun in the sentence to be translated, like in this German example, which is inconsistent: “The doctor” is translated with the masculine and “her work” with the correct feminine. [1]

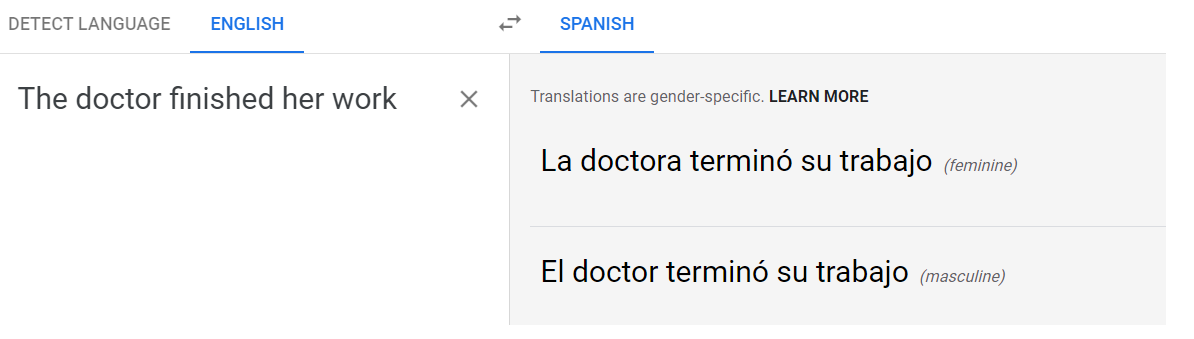

Google’s own scheme for addressing gender bias in machine translation is to provide two versions of the translation, one using a masculine form and one using the feminine one.

This makes a lot of sense when translating from a language without rich grammatical gender, like Turkish, to one where gender is usually specified, like English.

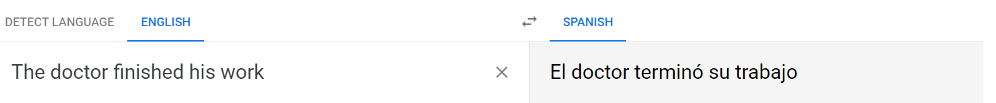

But when translating an example where the gender can be reasonably inferred from the original sentence, like this English-to-Spanish example, it seems like there should be a better way.

To emphasize, this isn’t just about a lazy reliance on stereotypes where there’s no other information to go by. This is about lazy reliance on stereotypes which run counter to the clear meaning of the source sentenc.

Is this a problem?

Well, the best case scenario is that this behavior is a little annoying or frustrating for users, which is already a bad start. But consider use cases for machine translation: drafting an email or a message in a new language, or reading a translated web page.

Translating with stereotypes misrepresents the words, and the writers, that are being translated.

How do we measure this effect?

The WinoMT test set is a test set for evaluating this problem when translating from English into languages with richer grammatical gender. It contains about 4000 sentences, each with two human-referent words and one pronoun.

The main objective is improving gender accuracy for the profession connected to the pronoun, although in the paper we also explore more detailed results, like the different performance on masculine and feminine labelled sentences.

It’s worth bearing in mind that the professions are chosen such that translating with the gender-stereotyping inflection for each sentence would achieve 50% accuracy.

Our approach: adapting an existing machine translation model to a “handcrafted” dataset

Machine translation models take a lot of time, computing power and data to work well. We want to avoid having to start from scratch any time we spot new examples of bad behavior.

But they can be adapted very quickly to a new set of example sentences. This is a widely used way to get a system that translates well in a particular “domain”, such as scientific papers, or documents from some individual customer.

Our idea was to define a “domain” of sentences that had equal numbers of male and female entities. [2]

For this, we define a very simple set of fewer than 400 sentences, following a template:

The [profession] finished [his|her] workWe pick professions from a previously published list. Every profession appears twice with masculine and feminine inflection in the gendered language.

Some of those professions might appear in the WinoMT test sentences, so we also create a set without those overlapping professions, mixing in adjective-based sentences instead:

The [adjective] [man|woman] finished [his|her] workResults here are for adapting to this non-overlapping “handcrafted” set, which has less opportunity to memorize professions.

Why not balance the original sentences?

While people have attempted “counterfactual augmentation”, or trying to balance English text in this way, it can get very complicated to do the same for grammatically gendered language, because so many words may require adjusting to stay grammatically correct.

Nevertheless, we also compare adapting to a form of “balanced” text from the original training set. First, it’s many times slower to create, and slower to adapt to.

And experimentally, we don’t find adapting to the “natural” counterfactual set improves WinoMT gender accuracy very much over the baseline model.

“Catastrophic forgetting” during adaptation: gender accuracy improves but general translation ability drops.

The seemingly inevitable trade-off of neural network adaptation is that the model learns to do new things, but loses the ability to do whatever it could do before.

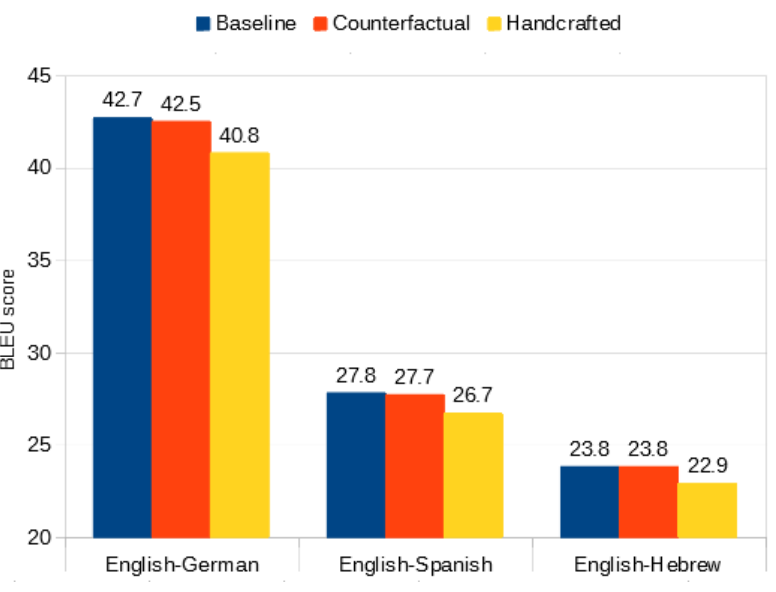

In this case, what it could do before is translate a wide range of sentences into a target language. Machine translation quality is measured by BLEU score, with 0 BLEU being complete nonsense and 100 BLEU being a translation that perfectly matches some human translation.

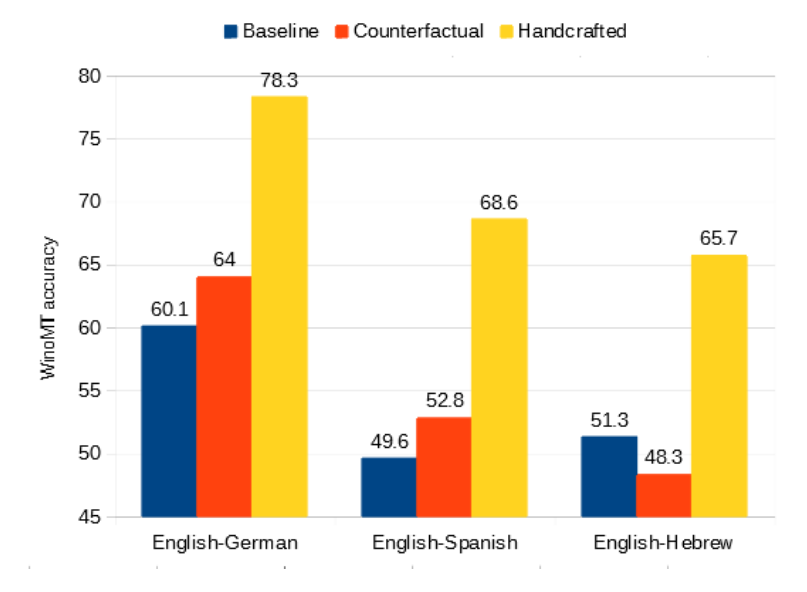

Checking BLEU score on standard test sets for the adapted models, we see the evidence of forgetting in reduced BLEU scores when strongly adapting to the handcrafted model.

One way to stop this is a regularization scheme like Elastic Weight Consolidation. That discourages the neural network from changing too much, but introduces a tradeoff. It forgets less, but it also learns less.

The other way we propose is to treat this as an error correction problem.

Idea: first adapt, then correct gender errors

The original model may be good at translating a wide range of sentences. But we know it struggles with human-referent gendered terms.

The adapted model can be highly specialized to translate these terms well. But most words are not human-referent gendered terms.

Our idea is to generate a first-pass translation with the original model, and then a second translation with the adapted model. But crucially, the adapted model can only change words in the original translation to other forms of the same word with different grammatical gender.

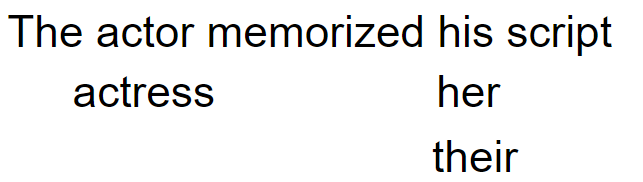

For example, in English, the model might be allowed to change between “his”, “her” and “their”, as differently gendered possessive pronouns. It could change between “actor” and “actress” as two gendered inflections of that word. However, it wouldn’t be allowed to change the word “his” to “actor”. And the words “the”, “memorized”, and “script” would all remain unchanged, because they have no alternate gendered forms in English.

A walkthrough for this process with links to a drive account with scripts and data can be found at our github.

Far more words have various gendered forms for the grammatically gendered languages we’re interested in, like German. Existing tools like spaCy can be used to collect these.

How well does it work?

We find this works very well! We see practically no decrease in BLEU on standard translation test sets. On WinoMT, the gender accuracy still improves dramatically. In fact, because we don’t have to worry about the forgetting trade-off, we can improve accuracy even more than in the plots above.

For English-to-Spanish and English-to-Hebrew, gender accuracy goes from about 50% — very close to random guessing on the binary WinoMT test set — to the mid 60s. For English-to-German, our best initial model, WinoMT accuracy improves from 60.1% to over 80%.

Overall we see about 30% relative accuracy improvement over the baseline with essentially no change in performance for sentences without gendered terms.

What next?

This investigation had very promising results. We used a very small amount of easily prepared adaptation data to focus an existing machine translation model on gendered terms, and potentially mitigate pre-existing gender biases. In terms of application, there are two particular avenues this paper left open:

One avenue relates to the type of gender inflections we considered. Human gender isn’t binary, and increasingly many individuals prefer to use pronouns and other terms outside the masculine/feminine defaults. However, many languages have only binary grammatical gender conventions for human-referent words. Could we develop a framework for flexibly-defined new gender inflections to extend — and evaluate — our approach?

The other avenue relates to how certain we can be about the gender of any given person referred to in an isolated sentence. As we noted before, it’s possible to come up with scenarios in which any combination of pronoun-entity links is plausible. But what if we know for certain that, for example, the doctor is female and the nurse is male. Can the approach described here make use of that information, with some kind of gender tag?

In a follow-up paper, Neural machine translation doesn’t translate gender coreference right unless you make it, we show that the answer to both of these questions is yes — under some circumstances. A writeup of that paper is now also up!

[1] Any example of human language has possible ambiguities. In this example, you could argue that the doctor could be finishing someone else’s work. For the purposes of this paper we focus on the explanation which doesn’t require external context. In a follow-up paper, we explore the possibility of controllable gender inflection, which removes this ambiguity.

[2] In this paper using only masculine and feminine grammatical gender allowed us to use WinoMT directly and compare to published results — in our follow-on paper we extend the idea and test set to the more complex scenario of introducing non-binary grammatical inflections.